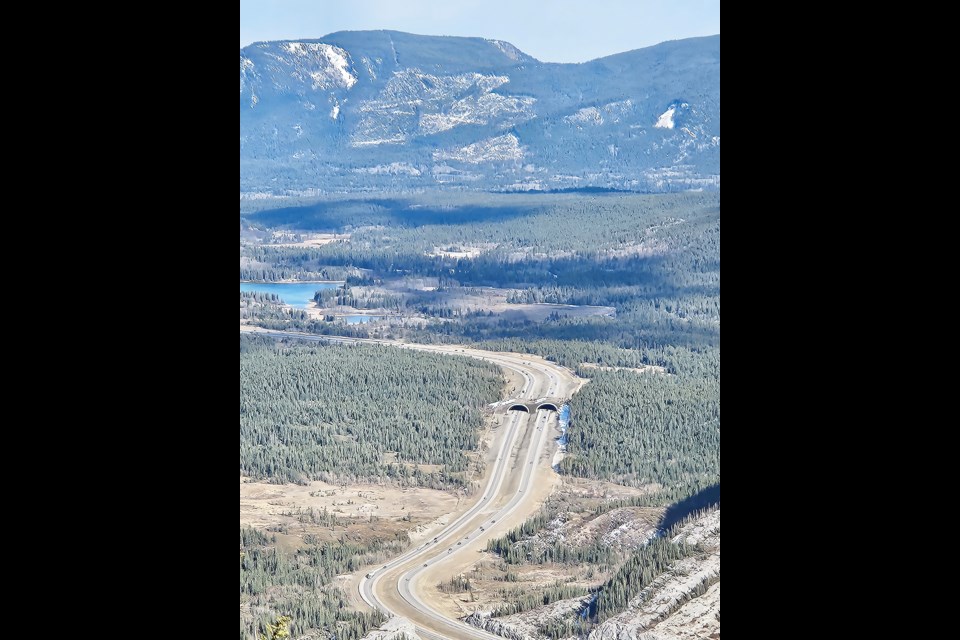

LAC DES ARCS – The wildlife overpass on the Trans-Canada Highway near Lac Des Arcs will have a new name.

The critical crossing over the busy stretch of highway will be known as the Peter Lougheed wildlife overpass after the former long-time premier of Alberta from 1971 to 1985. Lougheed’s government established Kananaskis Country and a provincial park was also named after him.

The official renaming took place Friday (June 13), with the crossing first being called the Bow Valley Gap then the Stoney Nakoda Exshaw wildlife arch.

Joe Lougheed, Peter Lougheed’s son and a member of Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) advisory board, said it was an “important ecological conservation tool” that will “ensure connectivity across the entire region, so animals can thrive with humans and development.”

During the announcement, MD of Bighorn Reeve Lisa Rosvold highlighted the overpass as “vital for wildlife connectivity in this region” and a critical area “for a wide range of wildlife.”

The crossing is the first wildlife overpass outside of a national park in Alberta, but there are no immediate plans to add additional overpasses or underpasses in the Bow Valley region.

Devin Dreeshen, Minister of Transportation and Economic Corridors, noted the ministry is continually reviewing data to identify collision-prone areas that need mitigation.

He said statistics from the provincial government show about 60 collisions a year along the stretch of highway, with the wildlife overpass estimated to reduce it by about 80 per cent.

From 2016-23, from the east gates to Highway 40 in Kananaskis Country, there were about 400 recorded carcasses. The numbers include Highway 1A and local roads.

“It’ll be interesting to see the data coming off of this,” he said. “If there’s any other locations that have similar collision rates that we need to prioritize, we can start to look at for a significant investment in other areas.”

Dreeshen added wildlife-vehicle collisions can cost about $300,000 a day in property damage, healthcare and highway maintenance costs.

He said the ministry gets annual reports on potential areas that may need wildlife crossings, with data ultimately feeding any recommendations.

Dreeshen pointed to the Alberta Wildlife Watch program as a collection of data to identify potential projects in the future.

“We’ve seen the success of wildlife overpasses in other areas in the national parks, so with our Alberta Wildlife Watch program we’re going to be reviewing other locations where we could have additional wildlife overpasses,” he said. “The fencing has to go along with the overpasses, but we’re in early stages of trying to identify other locations across the province.”

The factors being analyzed are traffic volume, number of wildlife-vehicle collisions, how long fencing would be needed to support a crossing and the overall cost. The provincial government has an ongoing project to twin Highway 3, where there’s been calls for wildlife crossings, that’s been broken into eight sections.

“We know they’re successful because they’ve been utilized. … The adoption by animals is going to change over time, but we have cameras set up to constantly monitor to see how successful it is,” he said. “It’s more data for us to be able to make decisions in the future.”

More crossings would help wildlife connectivity

The $17.5 million capital project broke ground in 2022 and was scheduled to open in fall 2023 after a detailed design had been done in 2020 and the project tendered in 2021.

However, the project was delayed multiple times into summer 2024 and the fall.

The delays were caused by design and safety concerns, the provincial government previously stated.

There are about 12.5 kilometres of wildlife fencing along the highway stretching to Dead Man’s Flats. There are jump-outs in the fencing so wildlife that get stuck on the highway can get back to safety on the other side of the fence.

The existing Dead Man’s Flats underpass was funded by the G8 Legacy Project and the Stewart Creek underpass will be a joint venture between Three Sisters Mountain Village and Alberta Transportation once it’s constructed in the coming years.

The Bow Valley is considered one of the four most important east-west wildlife connectors in the entire 3,200-kilometre length of the Y2Y region and one of two important connectors for wildlife in Alberta.

Deer, elk, bighorn sheep, moose, cougars, lynx, wolves, black bears and grizzly bears use the high quality habitat along the Bow River valley bottom to move between the protected areas of Banff National Park and Kananaskis Country.

“Any jurisdiction that takes it on as a project means they can replicate in other jurisdictions where it’s needed,” said Adam Linnard, Y2Y’s manager of landscape protection. “The first one is always the hardest and seeing this complete is a point of hope for seeing more of them in the valley, but also Highway 3.

“A highway of this size with this much traffic on it is functionally a wall. If it doesn’t kill [wildlife], it’ll turn [wildlife] away. Having these mitigations of fencing and crossing structures turns what’s in a wall into reconnected landscape. Realistically, the species we have here aren’t going to survive if we don’t provide them with this kind of help, given everything we’ve done to develop this region.”

More than 30,000 vehicles travel through the valley on the Trans-Canada Highway each day during the summer. It also serves as a significant economic transportation corridor between Alberta and B.C.

A 2012 study by Miistakis Institute and Western Transportation Institute identified 10 sites along a 39-kilometre stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway from the east gate of Banff National Park to Highway 40, recommending fencing and associated underpasses.

The study called for one overpass at Bow Valley Gap east of Lac Des Arcs. That section of highway has historically seen the highest number of wildlife-vehicle collisions in the entire study area.

In Banff National Park, there are 38 wildlife underpasses and six overpasses along an 82-kilometre stretch of highway from the national park’s east entrance to the border of Yoho National Park – the most wildlife crossing structures and highway fencing in a single location on the planet.

The wildlife exclusion fencing that parallels the highway throughout the park has reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions by more than 80 per cent and, for elk and deer alone, by more than 96 per cent.

For wildlife like grizzly bears and wolves, it may take up to five years before they feel secure using newly built crossings. Elk were the first large species to use the Banff crossings.

Research in Banff has shown that grizzly bears, elk, moose and deer prefer wildlife crossings that are high, wide and short in length, including overpasses. Black bears and cougars seem to prefer long, low and narrow crossings.

Linnard said a large landscape view in establishing a system that wildlife corridors are connected to in the region is the best option in helping wildlife move safely.

“Ultimately, that’s the only way wildlife is going to survive. In the Bow Valley, we would hope for a systemic approach,” he said. “Fencing is good, but in order to help with connectivity, we do need to see some more crossing structures.”

He highlighted the partnership with the Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation was “critical for this overpass to happen,” and Indigenous involvement should be a priority for any future wildlife crossing.

Calls for additional crossings near Canmore

A wildlife fence from the Banff National Park east gates to the Bow River bridge in Canmore will break ground in 2025.

Once completed, the wildlife fence will be about 2.5 metres high and run 10km in length.

The capital project was part of $15 million to be spent over a three-year period to address problem areas for vehicle-wildlife collisions.

However, there were no planned wildlife crossings with the fencing.

Stephen Legaree, an environmental specialist with Alberta Transportation, told Canmore’s committee of the whole last year industry standards for crossings are every two to six kilometres.

He said an underpass in the national park is taken into account for the fencing work. Legaree also said a culvert structure near Harvie Heights will allow wildlife to cross Highway 1A when it goes underneath the Trans-Canada Highway as well as underneath the Bow River bridge.

Earlier this year, the Bow Valley human-wildlife coexistence roundtable called for more viable crossings for wildlife in the fencing plan.

The roundtable, which has municipal, provincial and federal representatives, requested existing culverts or bridge underpasses to be utilized for helping wildlife movement.

The provincial government also began the planning stages for two wildlife crossings on Highway 1A between Exshaw and Canmore in 2024.

One is an underpass east of Elk Run Boulevard and the other is an overpass adjacent to Gap Lake. The projects retrofit existing drainage to allow wildlife to cross the highway from the Fairholme Range in the north to Bow Flats Natural Area and Bow River in the south.

From 2019-24, there had been 62 “large-bodied wildlife” such as deer, black bear, elk, bighorn sheep and wolves hit and killed in vehicle collisions between Canmore and Highway 1X.

“We believe that uninterrupted fencing will impede wildlife movement and create the unanticipated consequence of reducing wildlife populations,” wrote Canmore Mayor Sean Krausert, Rosvold and Banff Mayor Corrie DiManno to Dreeshen and Environment and Protected Areas Minister Rebecca Schulz.

They stated new or retrofitted crossings to help connectivity “should be a priority for the Alberta government and this should not wait for regular maintenance or structure lifespan upgrades.”