If you lived in Philadelphia in the early 1900s, you likely would have known Mary Schäffer as a polite socialite. But if you lived in the Canadian Rockies, there’s a good chance you knew her as Yahe-Weha, or Mountain Woman.

In the early 20th century, Schäffer spent years exploring the Canadian Rockies in and around Jasper and Banff. Her dual lives—one spent in upper-class Philadelphia drawing rooms, the other in backwoods mountain camps—and gender have made her a compelling figure, and her contributions to early exploration carved her a place in history as one of the most important early explorers of the area.

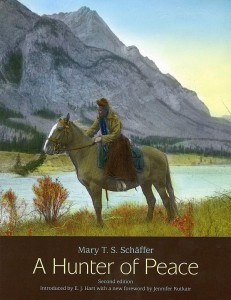

Banff’s Whyte Museum recently overhauled and re-released the book that sparked the scholastic re-interest in Schäffer. A Hunter of Peace is a record of Schäffer’s journey as she searches for and eventually finds Maligne Lake, chronicling the beauty of the landscape, and the people she encountered on it, in both prose and intensely captivating lantern slides.

The second edition of the book brims with new content, including dozens of newly colourized and updated prints of Schäffer’s lantern slides, and an unedited version of her manuscript detailing her 1911 expedition to Maligne Lake.

According to Elizabeth Kundert-Cameron, the museum’s librarian and manager of reference services, while the new edition of the book is a more up-to-date reflection of 2014 archival and publishing standards, it’s also a much truer representation of Schäffer’s work.

She explained that when the book was first released in 1980, much of Schäffer’s voice was left out. The book contained far fewer of Schäffer’s lantern slides, a significantly edited version of her 1911 manuscript, and it left out her forward completely.

Kundert-Cameron and the committee that revamped the work took great care to put as much of Schäffer back into her own work as possible, breathing her life back into the pages.

They also made several changes to make it more accessible—including a table of contents and index—and significantly beefed up the book’s citations and references.

“It’s more of Mary now in it,” Kundert-Cameron said. “It’s an even better testament to Mary’s talent, especially as a photographer.”

And according to the museum’s head archivist, Jennifer Rutkair, Schäffer’s talent was instrumental in building the popularity of the Canadian Rockies in the early 20th century.

“Her travel writing and lantern slides had a tremendous impact on the popularity of this area and the growth of tourism,” she said.

Rutkair explained that before the popularization of 35mm cameras, lantern slides were a popular form of not only entertainment, but education. Schäffer’s beautiful slides (and her accompanying lectures) brought the stark detail of the Rocky Mountains to audiences across North America, and had a huge impact on tourism within the parks.

Schäffer was also the driving force that ensured Maligne Lake’s continued protection, by having it included in the boundaries of Jasper National Park.

Today, Maligne Lake is the subject of a significant amount of writing and endless photographs. Its popularity is almost entirely due to Schäffer’s work, and that work still stands out 100 years later.

Trevor Nichols

[email protected]