There's a long list of Jasperites who fought for their country in the early 20th century, and each Remembrance Day we turn our thoughts to them.

But, for a brief period during the First World War, Jasper was also part of a darker wartime history, one that is just as important to remember.

It's a history not of the noble sacrifices made by Canadian soldiers, but of the forcible confinement of large swaths of our population, perceived to be a threat to national security.

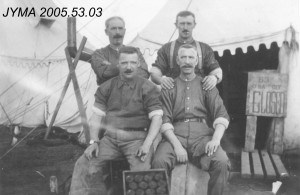

In 1916 Jasper was the site of one of these internment camps, which housed more than 200 men. And although they were technically considered “prisoners of war,” in reality most of them were unemployed or destitute Ukrainians scooped up by the government and shipped to Jasper to perform physical labour.

The camp opened Feb. 8, 1916. Plunked on a patch of land between the Athabasca River and train station, its 14 buildings were enclosed by more than 9,000 kg of barbed wire, circling the lot on a five-metre-high fence.

The men slept and ate in 25-by-40 ft bunkhouses, each with bunks for 50 men. The beds were built two tiers high, and arranged so the prisoners slept with their heads facing the wall.

Officials in Jasper did not buck at the thought of POWs in the park—they actually welcomed them. After all, where else could they find hundreds of men to perform the punishing physical labour necessary for the park's expansion?

There was excitement in the air, and suggestions flew that development in Jasper National Park—which had been stunted by the wartime crunch—would reach unprecedented heights.

Even the newspapers wrote almost gleefully about the construction of the camp. The Edmonton Journal argued “life at the camp is not one continuous round of sightseeing for the prisoners. The amount of work accomplished is only limited by the duration of the war.”

And it's easy to see why that perception existed. The prisoners were expected to work six days a week, for five cents a day—a rate that was as much as $1 short of pre-war wages, and $1.20 short of enlisted men's salaries.

And it was hard labour, too. During the cold winter months there was too much snow to build roads, so prisoners spent months in the bush cutting 5,500 fence posts, by hand, for nearby Willmore Park. Others spent their days hacking a ditch out of the frozen ground for a water main to the townsite.

One report by Maj. A. E. Hopkins detailed the work completed by prisoners on March 19, 1916. That day, 75 of the men spent the day cutting fence posts in the bush, 25 dug a ditch, 20 worked at the water main in Jasper and 10 hauled wood. The rest cleaned the camp.

By the time the weather was warm enough for roadwork to begin, the prisoners were so fed up they staged a hunger strike. Later, they changed tactics, refusing to do any work, even as guards reduced their rations.

This was the first time a national park internment camp had been hit by a strike, and the public was not happy. But the general in charge told the guards that civilian prisoners could not be compelled to work, or punished for not doing so.

This meant the Jasper commandant could do nothing but meekly suggest to the prisoners that the work was good for their health and well being, and reduce their rations. Reports suggest this was not a compelling argument.

The stalemate was finally broken in May, when 27 prisoners agreed to help build a camp at Maligne Canyon.

But on Sunday, May 21 the new camp proved to be a headache for officials, when three prisoners escaped.

According to a testimony by Lt. H. R. Mountfield, the prisoners were sleeping together in a tent “some distance from the site of the permanent camp.” The camp was not yet surrounded by barbed wire, and because it used the Athabasca River for drinking water, latrines had to be put up farther away, in thick brush.

Mountfield guessed that around 5 p.m. the prisoners used that route to flee. Shortly after, Martial Law was declared in Jasper.

Prisoners No. 46, Joe Walla, No. 13, Tony Pyziak, and No. 24, Lorenz Maki, tasted about 48 hours of freedom, before they were caught and returned to the main camp.

After the incident, guards stepped up their coercion of the prisoners, and before long work began on the Maligne Lake Road. About five kilometres of the road were completed, which is remarkable considering one guard's report, which complained that the men wouldn't work “without actual force ... and did everything under protest.”

In August 1916, due to ongoing tensions between guards and prisoners, the camp was shut down and most of the prisoners let go.

Of the 207 men held at the camp, 185 were released. Some went back to the communities that initially recommended them for internment, but many ended up working for railway stations and mining companies.

Twenty-two of the men—including the three escapees—were shipped to different camps and held longer.

It's a chapter of Jasper's history many might like to forget, but just as important as remembering the war's heroes is remembering its injustices.

On Saturday, Oct. 12, 1996, the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association placed a plaque in memory of the old camp. It's still there today, ensuring that this short episode in the park's history is never lost.

Trevor Nichols

[email protected]