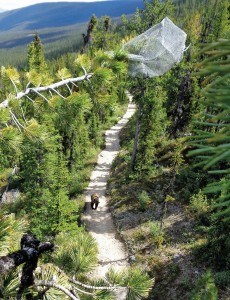

A large grizzly bear recently kept an eye on things, as Parks Canada staff worked high in the surrounding whitebark pine trees. Satisfied that the cone-caging activities were in the best interest of its habitat, the bear gave a thumbs-up and meandered on.

A large grizzly bear recently kept an eye on things, as Parks Canada staff worked high in the surrounding whitebark pine trees. Satisfied that the cone-caging activities were in the best interest of its habitat, the bear gave a thumbs-up and meandered on.

OK, the thumbs-up part is a stretch, but the work is helping Jasper’s high elevation habitat through the conservation and restoration of a key species—whitebark pine.

Listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act and found in some of the harshest and most stunning high-elevation areas of our Mountain National Parks, whitebark pine trees are a keystone species. This means that the species is much more important to the ecosystem than its frequency suggests.

Its strong roots, nutritious seeds and sheltering branches help many other plants and animals survive. This includes birds like the Clark’s nutcracker, red squirrels, grizzly and black bears, and other mammals. Whitebark pine roots stabilize soil to reduce erosion and hold snow to control water flowing from the mountains in the spring.

Unfortunately, a disease called white pine blister rust is killing these trees. It was introduced to North America from Europe in the early 1900s and has since spread and infected most whitebark pine stands. The rust infects the tree through its needles and then spreads into the tree’s phloem—the living tissue that carries nutrients. As the infection grows, the bark and phloem die.

The good news is that we think at least some of the trees are resistant. For the past three years, Parks Canada staff has been searching for disease resistant trees and protecting some of their cones until seeds mature. Trained staff use ropes and harnesses to carefully climb trees that have potential rust-resistance or rust tolerance, and secure specially designed cages around a selection of cones to keep squirrels and birds out as the cone develops.

A fear of heights is not an option here.

The cones are then collected in late summer, and the seeds within are used to plant and grow seedlings in the wild.

Parks is taking additional action to restore whitebark pine habitat and protect the trees. Using prescribed fires, Parks is restoring the open spaces this tree needs to grow, following decades of fire suppression that has allowed shade loving trees like spruce to take over.

To protect blister rust resistant trees from the additional threat of mountain pine beetle infection, staff are placing a pheromone packet of verbenone on trees to trick the beetles into thinking the tree is already infected and to look elsewhere for a suitable host.

Whitebark pine stands are a part of some of the most beautiful high mountain landscapes in North America.

Want to check out this unique tree for yourself?

Head out on the first few kilometres of the Astoria Trail, the first kilometre of the Geraldine Trail, or up to Brussels Campground on the Fryatt Trail, and look for long needles in groups of five.

Did you know?

Whitebark pine and the Clark’s nutcracker have evolved together, depending on each other for survival in the harsh climate of the sub-alpine. Clark’s nutcrackers use their long, pointed beaks to break apart the large whitebark pine cones and remove the seeds. The birds cache the seeds to ensure a reliable source of food through the winter. While squirrels cache whole cones in middens, Clark’s nutcrackers select areas likely to remain snow free. Coincidentally, these open, sunny areas favour whitebark pine germination and growth.

A single bird is capable of caching thousands of seeds each year. Caching pine seeds just below the soil’s surface, Clark’s nutcrackers use adjacent rock and wood debris to create memory maps that assist them in relocating the seeds when needed. Approximately half the seeds are overlooked and many of these germinate and grow into pine seedlings.

Parks Canada

Special to the Fitzhugh