Parks Canada safety training pushes employees to the limit

As he rumbles down the highway in his Parks Canada car, John Wilmshurst speaks in a strained voice.

He’s on his way to Whistlers Campground, explaining the situation as he drives. A young girl is missing, her father is AWOL and her distressed mother is at the campground, taxing Parks Canada’s resources.

Several two-person strike teams have been deployed to find the girl, and in the incident command room Visitor Safety Specialist Max Darrah is on the radio keeping everyone in line.

More than 25 Parks employees are in on the operation, and the fact that it’s all a simulation does little to reduce their stress.

At the start of every camping season, Parks’ visitor safety team undergoes intensive multi-day training, designed to prepare them to keep visitors safe throughout the summer. The day before, the crew had gone through what Wilmshurst calls “startup training,” and today they are putting that training to the test, responding to multiple, overlapping scenarios over a short period of time.

The idea is to stretch the team’s resources to the absolute limit, forcing leaders to split their personnel and send the right people to deal with each crisis as it arises. Earlier that day the team responded to a simulated grizzly mauling near the golf course, while at the same time conducting a high-angle rescue at Old Fort Point.

“They’re really stretching us, and that’s the point,” says Wilmshurst, as he rolls into the campground, where the “staging area” for the search is set up. Visitor Safety Specialist A.L. Horton talks into a two-way radio, and beside him someone pours over a map featuring three red circles indicating the search areas.

“One of the things we really pride ourselves on here in Jasper is that everyone gets involved,” Wilmshurst says, explaining that everyone from visitor experience personnel, to scientists like himself and visitor safety specialists are out in the field for a rescue.

The actual visitor safety team consists of just seven specialists, and when a crisis arises they are the ones who take on leadership positions. But Wilmshurt explains that all kinds of other people are involved in the auxiliary parts of the operation: hauling equipment, delivering lunches, controlling the search area and talking to curious park guests.

“We get everybody mobilized in the effort because we know that if we have a real incident like this it’s vital to get everybody involved,” he says, explaining that with 120–140 visitor safety experiences taking place each year, it’s important everyone in the organization feels comfortable when the pressure is on.

Last year alone, he says, Parks responded to more than a dozen “major events,” including the search for a missing girl that almost lasted into the night.

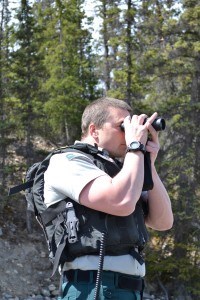

Down on the beach, Joe Storms—part of a strike team combing the riverside—slowly scans the water through a pair of binoculars.

“We’re looking for areas of concealment or entrapment,” he explains. It’s not good enough to glance at the river as he walks by, because shifting water levels can fool the eye. To ensure he misses nothing, he needs to focus on one area of the river for an extended period of time.

This scan reveals nothing, so he and his partner continue picking their way down the beach, stopping occasionally to stare out at the river.

On the way back to the staging area, Wilmshurst explains that for major operations Parks uses what’s called the Incident Command Structure—a quasi-military system in which everyone is assigned a role.

“It’s a really effective way to deploy people in a rescue scenario. Quickly, everybody knows their role, everybody knows where they fit in the structure, who’s going to be giving them direction, and to whom they should look for direction.”

It’s very regimented, he explains “and it has nothing to do with where you are in the Parks Canada hierarchy.

“So for instance, I’m the Resource Conservation Manager; I’m all these people’s boss, but I’m not the boss of this particular incident. That is Max Darrah, who is in charge, and I take directions from him.”

At the staging area a group of Parks employees crowd around a picnic table, murmuring into two-way radios. The girl—for the purposes of the simulation, a floppy, toddler-sized doll—has just been found unresponsive, and a strike team is administering CPR.

Before long she is whisked away to an ambulance, and the teams start packing it in.

A few hours after the training winds down, about two dozen Parks employees crowd into the “war room” for a debriefing.

“We wanted to really try and tax the group,” Horton, who helped design the three scenarios, tells the crew. The team then goes around the table, taking turns talking about their experiences and giving feedback.

A few suggestions are thrown out—the “distressed mother” says she sometimes felt ignored and someone cautions everyone to be aware of the distinction between “patient” and “victim”—but for the most part people feel things went smoothly, and are happy with how the scenarios played out.

Ryan Bray, who filmed the day’s training for Parks, says he was impressed with how professionally everyone acted, and how well they upheld the Parks Canada image, while “staying in the scenario and keeping it real.”

“I really hoped that we would get a lot out of this, and I think we did,” Horton says as the briefing winds down. “I’m proud to be a part of this team.”

Trevor Nichols

[email protected]