This is a story about Agnes Harragin, who—with her sister Mona, and muscled with female persistence, knowledge and hard work—became the first female horse guide in the national parks. It was the 1920s! I’ve searched for any evidence that she was a skier, and came up with holes in my bases.

It is, however, of little consequence. There’s no doubt in my mind that if she had decided to ski, she would have charged and ripped like the true pioneer athlete she was.

Part Two: Parking lot promise

Many a deal is done, promises made, routes concocted and ski trips planned in the most bizarre place—in an ordinary and inconspicuous parking lot.

This particular parking lot promise was devised with a mandatory after-ski beer in hand in the Bald Hills parking lot up at Maligne Lake. These conference rooms have no outside heating or soft seats and are rarely plowed, with vehicles backed haphazardly into spots they hope to be able to get out of at the end of the day.

Ski racks, stickers on windows and Thule boxes are clues to the eye of a savvy skier as to the intent of the outing. A quick, discreet peek inside confirms activity. Coffee cups, extra gear, maps and discarded clothes are thrown about the inside of the vehicle—all an indication as to who is out there: skiers!

In that parking lot we made a decision. We all got sick of saying, “You know that creek? The one that drains south out of Little Shovel Pass? Yes, the creek that we thought was Evelyn Creek, but it’s actually a creek that drains into Evelyn Creek.”

This must sound bizarre to a non skier, some hikers can’t comprehend, thinking to themselves, “It’s so obvious—just follow the trail.”

But in the winter, ski travel is a whole other dimension of obliterated bliss. Skiers follow summer trails in the lower elevations, but once the subalpine and alpine are achieved, the route changes dramatically, with the ski world as your oyster.

There are no blazes or trail markers showing the official, beaten way to travel. The route is up to the trail breaker, and that means having the skills, the knowhow and the gut feeling to lead the track up, gaining elevation steadily and safely through potentially perilous avalanche slopes.

The parking lot verdict and promise was to head for the unnamed creek—which we would later name Agnes Creek.

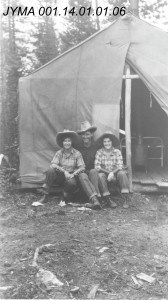

For anyone who’s familiar with Maligne Valley history, Agnes Harragin is a name you know. Agnes was one of two sisters—the other being Mona—who bravely and defiantly defied the rules of society, becoming the national park’s first female horse guides in the 1920s. There is a lovely lake in the Maligne area called Mona, but Maligne history buffs have long questioned and pondered why Agnes never received a sort of similar acclaim.

The two sisters rocked the Maligne Valley world, and the JNP world, in the late 1920s. The tiny in stature, but tough sisters loved and craved the hard working, outdoor life of horse travel and wilderness. They put in their time—probably learning the hard way, getting no help or advice from the cynical, skeptical male wranglers who were guarded, confident and cocky in their wilderness profession.

The sisters persevered; they roamed about the valley, exploring and pocketing many trail sense tidbits into their saddlebags. One evening, Agnes found herself sitting on the rocky shore of Maligne Lake, and reflected, “I felt a surge of happiness in having chosen to find myself a niche in such surroundings.”

The big boss in the Maligne Valley at the time was Fred Brewster, “Mr. Jasper” as he was referred to later on in life. He recognized and understood the desire, skills and work ethic of the mountain gals. Mrs. Brewster might also have had some influence over her husband, she spoke highly of the sisters, whose energy, determination, competence and trail savoir-faire could surely benefit all the dudes.

The sisters were hired to be the guides on the Circle Trip (Jasper to Maligne and back to Jasper). Mona said it best for both of them, verbalizing her true feelings about guiding, “Well, you see, I’ve never been afraid of anything. I don’t know why, but it’s true. Guiding turned out to be a lot of trouble and hard work. But for me, it was worth it. Just to know I could do the job.”

Agnes, we the skiers of JNP and the Maligne Valley hope that you concur. We have now informally named a very prominent winter route/creek/drainage after you—a creek that empties out of one of your old haunts: the Skyline Trail.

We think that you would agree to our logic and more importantly to the sentiment; the magnetic allure of why we keep coming back again and again to the Maligne Valley: to inhale the free alpine air, to have the wind pulverize the bejesus out of us, and to silently with velvet slippers on, slide over a white, often benign landscape in a total declaration of acceptance, exploration and ecstasy.

It was a parking lot plan, a parking lot promise.

Jasper Ski History is a four part series written by Jasper trail guru Loni Klettl. The first installation in the series titled "Trapper Creek, the rescue" appeared on Feb. 4.

Loni Klettl

Special to the Fitzhugh