Frieda Maynard pauses when she’s asked to spell her name. “That’s not my actual name,” she says, “it’s Lilian Jenny.”

Stripped of her language, culture and identity, the residential school survivor spent 13 years as a young Métis girl responding to a name that was never hers.

“It was a habit of the nuns and priests to change your name,” said Maynard, recalling her time spent at Grouard Indian Residential School, located near Slave Lake, Alta.

“They changed my name from Lilian Jenny, which is the name my mother had given me, to Frieda,” recalls the 75-year-old who now lives in Edson.

The renaming of Aboriginal children is a small, yet poignant example of the abuse, neglect and shame suffered by thousands of Aboriginal children who attended government funded residential schools across the country for more than a century.

The pain and suffering these children experienced amounted to cultural genocide, according to a damning report published by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, June 2.

The heart-wrenching 381-page report detailed the historical legacy of residential schools that saw more than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children ripped from their parent’s arms and placed in the care of the Catholic Church, which ran the schools.

The report also described the lasting impact the residential school system has had on survivors and their families and the impact it still has to this day in the form of racism, systemic discrimination, poverty and dying indigenous languages.

“They may have tried to kill the Indian in the child, but they didn’t kill my spirit,” said Maynard defiantly.

For Matricia Brown, a Jasperite who identifies herself as Cree, there is no doubt the abuse and neglect her mother suffered at Joussard Indian Residential School, also near Slave Lake, played a direct role in her suicide.

“I don’t think you can discount a suicide and a residential school upbringing and not think the two events are related,” said Brown, who was five-years-old when her mother took her own life.

Almost immediately after her mother’s death, four of Brown’s six siblings were apprehended by social services and put up for adoption.

“It’s a really hard story to talk about because it’s forever changed the dynamics of our family,” she said while fighting back tears.

“We still suffer a lot.”

Brown still remembers the day social services came to pick her and her brother up. She said they weren’t allowed to bring any personal belongings and had to leave all of their toys behind.

“It took a long time before my brother and I were integrated into our new social system,” she said, explaining they were the only Aboriginal students enrolled at the school.

“We didn’t speak English, we only spoke Cree, because we came from the Sturgeon Lake Reservation.”

She recalls her brother being bullied and teased in school because of his skin colour and a teacher telling her she wouldn’t get teased as much if she improved her English.

As a mother of two now living in Jasper, Brown still has a good relationship with her adoptive family in Calgary and has made it a point to educate her children about her Aboriginal culture.

“When I was 25 and pregnant I made a conscious choice to teach my children everything that was wonderful about my culture.” Today, she and her daughter make up a drumming duo called Warrior Women, through which they share their Aboriginal culture in schools and during community gatherings.

Brown has also found strength in reconnecting with elders such as Maynard, who would be the same age as her mother if she were still alive today.

“She lived my mother’s experience,” said Brown, “I talk to her a lot about the residential school system.”

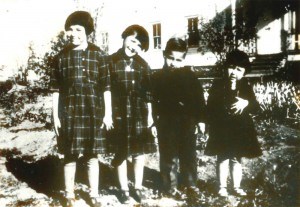

Maynard, along with three other siblings, first entered the residential school system as a two-year-old girl after her mother fell ill with tuberculosis.

“When you read the history of all of the native people and how horrible they were treated by government and churches, I’m certain my mother died of a broken heart,” she said, explaining her mother died at the age of 33.

“It still impacts my life today and I’m 75 years of age.”

She recalled being forced to study religion, discouraged from forming loving relationships with her siblings and being beaten until she was black and blue.

For Maynard, the commission’s report is welcome news, but only the first step in a longer journey toward reconciliation.

“There’s a lot of work to be done. It’s not the end, it’s only the beginning. There’s going to be people who hang onto their prejudicial attitude about Indians being lazy, drunk and stupid and there are also going to be some people who sincerely try to understand.”

She said the biggest impact on her community has been the lasting shame created by the residential school system.

“We lived by the code of silence. I was 40-years-old before I even admitted I had been in an Indian residential school. There was that much shame in just being who I was.

“The shame was not on me, the shame was on them and I know that today. Everyday I wake up and decide that I won’t let a horrendous past dictate what I’m going to feel like today.”

Using testimony from residential school survivors, former staff, church and government officials and archival documents, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission exposed thousands of horrifying stories, similar to Maynard’s.

“Anyone in an Indian residential school suffered horrendous losses—their culture, their language, their families and even the hair that is so treasured by native people.”

Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, estimated at least 6,000 children died in the care of residential schools, although only 3,201 deaths were officially recorded with the cause of death reported in fewer than 50 per cent of the cases.

The report also included 94 recommendations, including a Royal Proclamation of Reconciliation that, if implemented, would require the government to overhaul the relationship between Aboriginal peoples, the Crown and other Canadians.

It also demanded the Pope apologize to residential school survivors.

Today, Maynard has taken back her aboriginal identity and made it a point to learn about her ancestry.

“I’ve had a real desire to know what happened, why am I who I am today, and I have totally embraced my native culture,” she said, adding she is a trained addictions counsellor and studied native studies.

“It’s been very healing for me to participate in native ceremony and ritual to learn about my history.”

Paul Clarke

[email protected]