It’s like no other drive in the world.

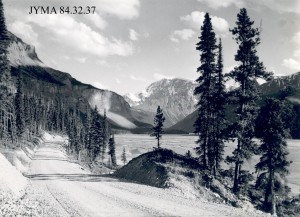

From sweeping valleys lined with emerald lakes to the dizzying heights of snow-capped mountains, the meandering 230-km journey from Jasper to Lake Louise has captivated generations.

Exactly 75 years ago, the Icefield Parkway, also known as Highway 93, opened to the public, ushering in an era of tourism to a region that remained isolated for centuries.

The history of the highway is as enchanting as the road itself, from stories about the men who first laid eyes on the Columbia Icefield to stories about the men who physically built the road.

Like all good tales though, this story begins by happenstance and a fabled peak.

Long before Canada was a country, First Nations and fur traders regularly traversed the mountain passes and valleys to hunt and trade in the area.

In the spring of 1827, David Douglas, a botanist working on behalf of the Hudson’s Bay Company, crossed the Athabasca Pass, a major trading route through the Rockies, north of the Columbia Icefield. During his expedition he decided to climb a nearby peak that he claimed rivalled the Himalayas.

The elusive peak, however, remained a mystery for subsequent explorers until nearly 60 years later, when, in 1884, professor Arthur Coleman, a geologist with the University of Toronto, visited the Rockies in search of the legendary mountain. Using Douglas’s journals and famed maps, he negotiated the Great Divide from Banff to Jasper House, in search of the mountain.

Although unsuccessful in his quest, he ultimately discovered what would later become the route of Highway 93.

Described as a “wonder trail,” the highway was the brainchild of Arthur Oliver Wheeler, the principle land surveyor in charge of plotting the border between Alberta and British Columbia in the early 1900s.

“Through dense primeval forests, muskeg, burnt and fallen timber and along rough and steeply sloping hillsides, a constant flow of travel will demand a broad, well-ballasted motor road,” wrote Wheeler in a 1920 journal entry. “This wonder trail will be world renowned.”

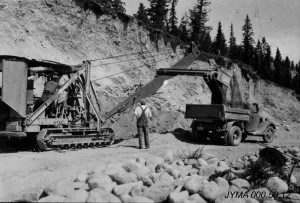

From his photo topographical surveys, construction of a single-track road began in 1931 as part of a depression-era public works program, putting men, machine and horses to work.

“The whole notion of a wonder road emerged because people came back and would tell stories of an extraordinary route through some of the most absolutely breathtaking scenery in the world,” said Bob Sandford, long-time Canmore resident and author of more than 25 books about nature, history and water in the Rockies.

“It became known as one of those places to go where you could come into contact with landscapes of such aesthetic power that it would be unforgettable.”

Completed in 1940, the road rivalled near by infrastructure projects including Johnson Canyon and Rogers Pass, built in the late 1800s in tandem with the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885.

“Surveyors went in with pack ponies, fording icy mountain streams to find a scenic route which would safely skirt the Columbia Icefield,” according to an article published in 1933 by Popular Mechanics.

Described in great detail, the magazine painted a picture of the slow, meticulous work that was required to complete the project, adding that construction could only be done in the summer due to its remote location.

“The most difficult stretch to build was the series of switch backs. For seven miles the builders had to hang onto sheer rock walls to dynamite the right of way. While work has been going on from both ends not more than 17 miles can be graded and surfaced each year.”

During the second world war, allied soldiers frequented the area to train for combat. The American 87th Mountain Infantry spent two months on the Columbia Icefield testing an over snow vehicle, while British and American soldiers practiced mountain warfare on the glaciers.

By the 1950s, the proliferation of automobiles allowed thousands of people to make the journey and see for themselves the breathtaking scenery. With tourism booming, places like Jimmy Simpson’s ‘Num-ti-jah’ lodge and the Brewster brothers’ Icefield Chalet became popular overnight stops.

Paved and realigned in 1962, the road opened up the Great Divide to thousands of more visitors, with attractions popping up all along the way. In 1969 Brewster began operating their snowmobile tours on the Columbia Icefields.

“Parks Canada is thrilled to commemorate the 75th anniversary of one of the top scenic drives in the world,” Parks Canada’s Visitor Experience Manager Pam Clark wrote in an email.

“The Icefields Parkway, like the rest of the Canadian Rocky Mountains UNESCO World Heritage Site, was designated for its exceptional natural beauty, abundant wildlife and outstanding examples of geological and landform processes.”

Stretching from Lake Louise to Jasper, the highway ascends to 2,067 metres above sea level at the Bow Pass before gradually descending to the mouth of several glaciers and the Columbia Icefield.

From there the highway skirts past the Athabasca Glacier and begins to climb, crossing the Sunwapta Pass at 2,035 metres, which marks the boundary between Banff and Jasper National Park.

Nearing Jasper, the road winds its way down to Athabasca Falls, before slightly climbing again to reach Jasper at nearly 1,200 metres.

“One of the greatest policy achievements in the entire country and certainly in the Canadian West is that when we began developing the west and selling it off we recognized there were places, in the Rockies particularly, that were of such aesthetic power and value we decided to set them aside,” said Sandford, who worked as a park naturalist for Parks Canada at the Saskatchewan River Crossing when he was 20 years old.

Today more than 1.2 million people travel the Icefield Parkway each year, mostly during the summer months.

“The whole sense of what these places bring to us and how they define our sense of identity is central to who we are.”

Paul Clarke

[email protected]