It all belongs

by Paula Klassen

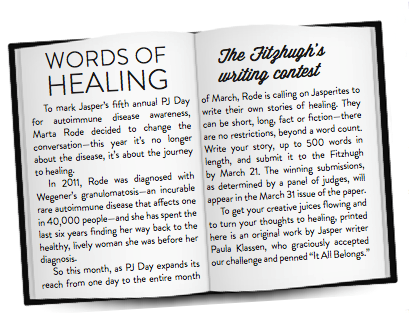

When Marta and Nicole invited me to write an article about healing, I had to chuckle because for the past year, I have been writing extensively about death. I don’t think that they knew this beforehand, but here it goes.

My curiosity of death led me to Stephen Jenkinson’s work. The subject of the NFB documentary Griefwalker, Jenkinson offered me a different way of approaching death and its essential connection to health. In our death-phobic North American culture, health is often grasped at as a possession or a right.

Jenkinson invited me to look at health as resting on a relational tripod that includes: our relationship with other humans, our relationship with non-humans, and our relationship with the unseen.

This is where healing becomes a much bigger phenomenon that does not exclude disease, or hardship or brokenness. Healing includes all of these things. Healing also includes dying.

Unfortunately, dying well is a piece in our cultural story that many of us have forgotten. And so, I read more about autoimmune disease.

Autoimmune disease is akin to having the army that is supposed to protect your homeland turn on you and pillage the land it lives on and kill its populations. It’s not a malicious attack but one based on confusion, and the inability to recognize self from non-self.

As I read what’s happening inside the body, I am first struck by the language of warfare in this description. Is it possible to fathom the notion of dying well in this context? Is the body truly confused or does it know exactly how it needs to proceed?

I approach the mystery of this disease with respect. Within the word mystery, I hear the subtleties of “missed stories.”

In viewing the body as a living, dynamic, open system, I ask, “are there ‘missed stories’ and where might they be?” I learn that the common thread that connects the hundreds of variances of autoimmune disease is the immune system, so let’s begin there.

According to Charles Eisenstein, author and self-described “de-growth activist,” stories can also be described as having a lifespan and an immune system.

The author of many books, including The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible, Eisenstein eloquently deconstructs the story of industrialization and reveals its bare bones. Simply put, he explains that we, as members of the modern world, are telling ourselves a story of separation. Suburbs and nuclear family units are examples within the design of our human communities that feed into this story of separation. As it becomes increasingly difficult to withstand the stress, the immune system of this story of separation is giving us important feedback. This feedback comes to us through the gift of crisis.

Crisis, as a gift? Let’s do some more word play.

If we trace the etymology of the word crisis back to its Greek origins, we can extend the lifespan of this word to animate something we may not have considered before.

Whilst many of us understand crisis as a medical Latin term—the turning point in a disease—crisis brought to its origins becomes a decision. When crisis is framed as a decision, my perspective on the immune system shifts.

Could the immune system of our collective story be bringing us directly to the sticking points that no longer serve life? Again, that relational tripod (that extends to the non-human and unseen) becomes an important piece to reconsider as I question the foundations upon which the health of my story rests.

I observe my own responses when I collide with this story of separation—the behaviours of denial, arrogance, withdrawal that I can, too easily, turn on automatic pilot. These tactics keep me believing that staying safe and small are the only ways in which I can ensure self-preservation.

Again, the mystery of this open, living, dynamic immune system commands respect and I recognize the gifts of different voices creating space for larger conversations. It is during these times of crisis where women like Marta Rode begin to enter into my life. I hear her questions. I see her courage as she dares to voice those questions. Aloud.

I feel her unabashed trust and adoration in this human community of Jasper. Simply put, Marta has disrupted my story of separation and here I am, showing up in my pyjamas!

Being in my pyjamas keeps it real. That vulnerability to be seen when I feel I may not be at my best. These are the salient conditions in which decisions present themselves and where we can choose to make contact with a bigger story.

Pressure points. Tipping points. When these moments of crisis begin to feel unbearable, I am discovering that the invitations to step into the centre of deep learning come to me faster and stronger. Grief becomes one of the assets I draw upon to be fully present to what is happening. This is when the face of death truly reveals herself to me and she is beautiful.

So allow me to bring death to the forefront once again as I share my unabashed trust in the non-human intelligence that includes my vision of community. The midwives who are birthing this death are called the mountain pine beetles. Quick and seamless, they are exponentially changing the expansive sea of evergreen to a rusty red.

Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP) describes the mountain pine beetle as spreading eastward across Canada’s boreal forest. It may be that the scale of the pine beetle’s presence shifts and, once again, creates the conditions for the warfare language of “infestation” and “attack” to enter our human conversations.

I am learning that defense patterns are first created in the human mind so I keep my eyes open, allowing myself to see how death weaves herself into the forest’s story.

I draw upon Jenkinson’s experiences once again. Serving at a palliative-care centre for many years, Jenkinson has sat with hundreds on their deathbeds. Time and time again, he witnessed a recurring pattern in the manner people were choosing to die. He observed the dying person trying to endure—to not die for as long as possible.

Reading more about the types of trees into which the mountain pine beetle burrows itself and creates life, I discover that they are usually pine trees older than 80 years—pine trees that, one might say, have been made to endure a worldview of not dying.

Could one tiny beetle be disrupting my story of separation?

As I allow myself to be in direct contact with this tactile living, breathing world, I see the wild intelligence of the forest’s immune system being animated. The seamless dance between life and death.

The beetle selectively going to the tree that is choosing to die. And, that tree is not only dying, but is able to die well knowing she is feeding the life of the beetle. Is this a part of what Jenkinson is suggesting to a culture who, in his words, chooses to “end without any ending” and to “go without any leaving.”

How close does crisis have to land for me to invite endings into my life?

Perhaps immune systems aren’t designed to defend, but to assist us in making clear decisions. In deciding that it all belongs, I look at the pine tree’s death differently and get a glimpse of being seen with holes and connected with the whole.

Could it be that it all belongs? Sparkles and shadows. Fire. Pine beetles. Bed bugs. Buskers. Syrians. Moberlys. Grief. Bliss. From the belly laughter. Questions that create discomfort. What about cougars, too? Could it be that it all belongs?

We might need a miracle to allow for such a possibility. Miracles are what we all secretly crave when we speak of healing. Whereas many view miracle-making as the work of an external divine source. I am wondering if Marta Rode and the mountain pine beetle are directing us to the miracle-making happening in our midst.

As my story of separation is disrupted, I find myself witnessing mysterious causalities that I cannot even fathom. As I remember, turn towards, and invite the hand of death to work in my life, I am creating space for miracles to happen. In this light, miracles are what was impossible from an old understanding and possible from a new one.

Our stories provide us with the opportunities to heal ourselves, our relationships with one another and the planet. And it begins with… it all belongs.

Paula Klassen

Special to the Fitzhugh